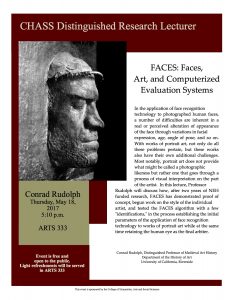

FACES: Faces, Art, and Computerized Evaluation Systems

FACES: Faces, Art, and Computerized Evaluation Systems

This event is sponsored by the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences

Conrad Rudolph

Thursday, May 18, 2017

5:10 p.m.

ARTS 333

In the application of face recognition technology to photographed human faces, a number of difficulties are inherent in a real or perceived alteration of appearance of the face through variations in facial expression, age, angle of pose, and so on. With works of portrait art, not only do all these problems pertain, but these works also have their own additional challenges. Most notably, portrait art does not provide what might be called a photographic likeness but rather one that goes through a process of visual interpretation on the part of the artist. In this lecture, Professor Rudolph will discuss how, after two years of NEH funded research, FACES has demonstrated proof of concept, begun work on the style of the individual artist, and tested the FACES algorithm with a few “identifications,” in the process establishing the initial parameters of the application of face recognition technology to works of portrait art while at the same time retaining the human eye as the final arbiter.

CHASS Distinguished Research Lecturer

Event is free and open to the public.

Light refreshments will be served

in ARTS 333

Conrad Rudolph, Distinguished Professor of Medieval Art History

Department of the History of Art

University of California, Riverside

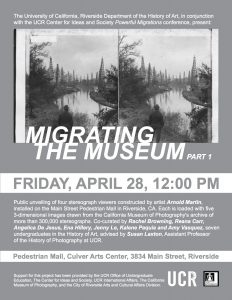

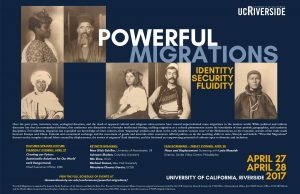

The University of California, Riverside Department of the History of Art, in conjunction with the UCR Center for Ideas and Society Powerful Migrations conference, present:

The University of California, Riverside Department of the History of Art, in conjunction with the UCR Center for Ideas and Society Powerful Migrations conference, present: Brink Carrot Lecture Series presents:

Brink Carrot Lecture Series presents: On Building a Career in Expanded Academia

On Building a Career in Expanded Academia

The Material of Form: Concrete Art during the Second Industrial Revolution

The Material of Form: Concrete Art during the Second Industrial Revolution